Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC) is a tool which identifies and interprets the varying historic characters of an area, looking beyond individual features, to understand the whole landscape and townscape. It helps to reveal patterns and connections in the landscape and to interpret the ‘time-depth’ of the now modern landscape.

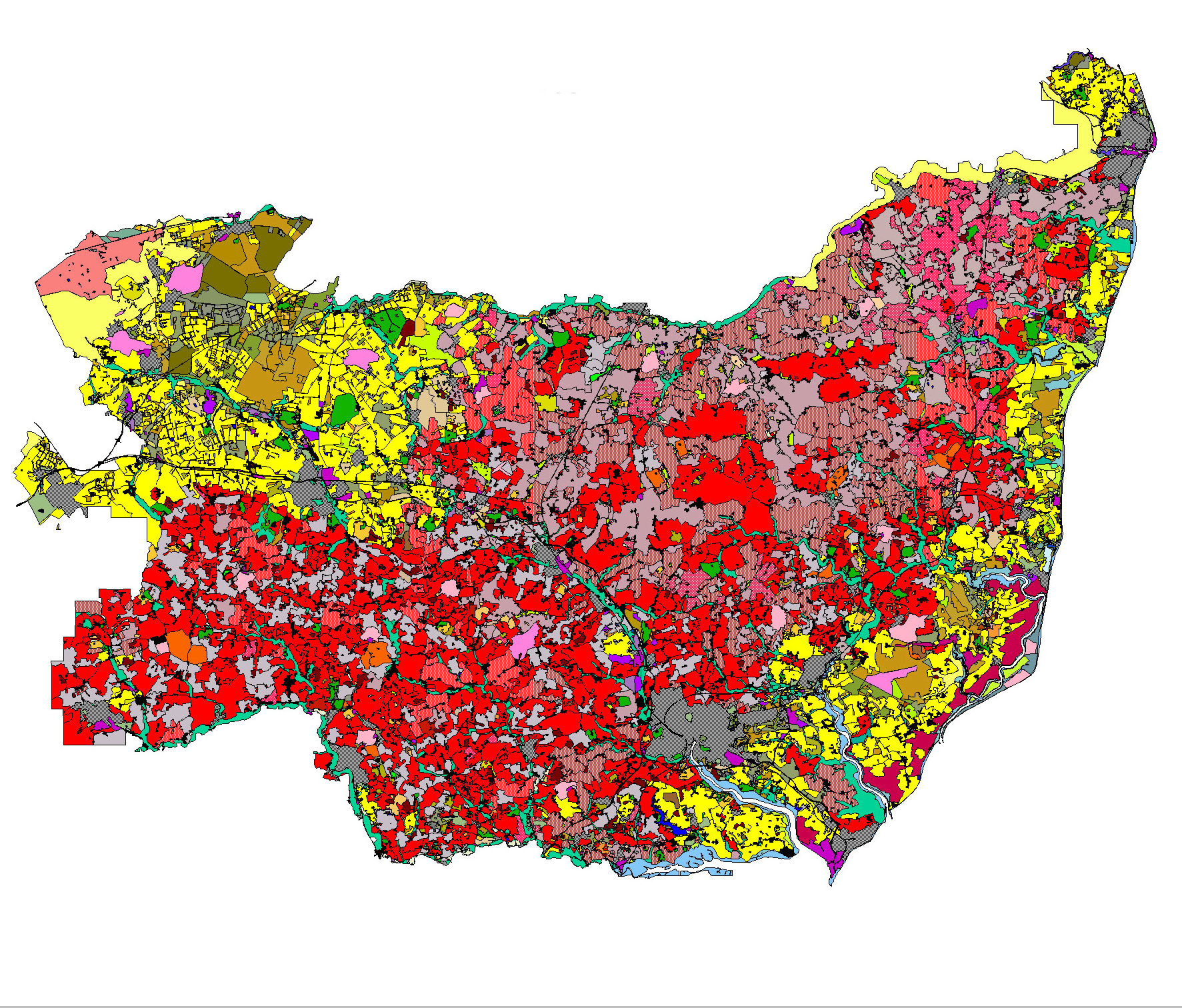

Displayed visually as a colour-coded digital map, it provides new ways of understanding and managing the historic landscapes, particularly as an analytical tool for historic landscape studies, informing development strategies and land management schemes, and enhancing the Historic Environment Record data.

The HLC map of Suffolk was compiled in 1998-99 by Matthew Ford as the first part of a wider East of England HLC Project covering Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk. The work was undertaken by the Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service and funded by English Heritage (now known as Historic England). The map was enhanced by Edward Martin in 2001, 2002, 2005 and 2008.

For further and detailed discussion of the Suffolk historic landscape character types in the wider context of the historic landscape of East Anglia see: E. Martin and M. Satchell, Wheare most Inclosures be. East Anglian Fields: History, Morphology and Management, East Anglian Archaeology monograph series no. 124, 2008

Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service hold the digital Geographic Information System (GIS) version of the map.

Other Projects

The Suffolk Historic Landscape Characterisation data has contributed to several other projects focusing on landscape assessment.

Suffolk Landscape Character Assessment

The Suffolk Landscape Character Assessment identified 30 distinct types of landscape in Suffolk. It was designed to support the maintenance and restoration of the landscape, particularly through the planning system, as well as to promote a wider understanding of Suffolk landscapes.

East of England Landscape Typology

Landscape East brings together landscape, biodiversity, geodiversity and spatial planning interests to steer the development of the East of England Landscape Framework. Their Landscape Typology records the varied landscapes of the East of England.

Preview the Map

Read the Character Types below to interpret the map.

Image Preview: Historic Landscape Characterisation Map. Key: Yellow = late-enclosed landscapes (18th and 19th centuries)/ Red = early-enclosed landscapes (pre-18th century, probably medieval or earlier)/ Grey = areas with considerable 20th-century landscape change

Character Types

The Suffolk historic landscape types operate at two different levels.

- A set of 14 broad types which give a basic characterisation; due to their broad nature these types generally carry a high confidence rating.

- A nested set of 77 sub-types that give a closer definition of the broad types; because of the higher level of interpretation needed to assign these sub-types, they generally carry a lower confidence rating.

The Suffolk HLC map can be used at either the broad types or the sub-types level.

A description of all the different character types and sub-types is given below.

Type 1.0 Pre-18th Century Enclosure

This category refers to land that was enclosed into fields for agriculture before 1700. In most of Suffolk the landscape is one of ‘ancient enclosure’, in contrast to areas like the Midlands, where extensive areas of common fields (large ‘open’ fields subdivided into separately-owned strips) were enclosed using parliamentary acts in the 18th and 19th centuries. In many of the areas of ‘ancient enclosure’ in Suffolk there is little evidence for a medieval phase of common-field farming: some areas had limited areas of common fields (as in north Suffolk) but in others there were none (as is often the case in south Suffolk). The identification of these earlier landscapes, which date back to medieval and in some cases even earlier, was a priority behind the development of the HLC mapping. These earlier landscapes are of great historic significance and have different management needs to later field systems.

-

1.1. Random Fields

1.1. Random Fields Landscapes made up of fields that have an irregular pattern (i.e. without any dominant axis). Many were in existence by the medieval period, but could be earlier. Boundaries are usually take the form of species-rich hedges (normally coppiced not laid) with associated ditches and banks. Areas with this field pattern are probably some of our earliest farming landscapes.

-

1.2. Rectilinear Fields

1.2. Rectilinear FieldsThis is not a dominant type in Suffolk. Landscapes of this type are made up of fields that tend to be small and rectilinear in shape, forming patterns that resemble the brickwork in a wall. They tend to exist in isolated pockets within more extensive areas of other types of early enclosure, and probably indicate relatively late episodes of field creation or re-organisation, although still pre-18th century, within earlier surroundings.

-

1.3. Long Co-Axial Fields

1.3. Long Co-Axial FieldsLandscapes made up of fields where a high proportion of the boundaries share a dominant axis. This takes the form of long, slightly sinuous lines that run roughly parallel to each other for considerable distances. These lines usually run at right angles to a significant watercourse. Co-axial systems are not all of the same date – some in valley-side positions may represent very early farming boundaries, but others on the clay plateaux are likely to be medieval in date (as in parts of the South Elmhams).

-

1.4. Irregular Co-Axial Fields

1.4. Irregular Co-Axial FieldsLandscapes where many of the boundaries share a common axis. They share many of the characteristics of long co-axial fields (sub-type 1.3) but lack their overall regularity and their boundaries are often only approximately parallel. The systems vary in size, merge in and out of one another, and generally fail to follow one particular aspect or angle. In some cases these systems represent the early, piecemeal, enclosure of common fields.

-

1.5. Former Medieval Deer Park

1.5. Former Medieval Deer ParkDeer parks were important symbols of lordship in the medieval period and normally consisted of areas of woodland, wood pasture and open grassland (launds), bounded by banks and ditches with hedging and/or wooden fences to form a ‘park pale’. Park pales frequently have curved outlines as this was the most economic way of enclosing large areas. Deer parks were frequently situated on upland clay areas unsuited to agriculture and can therefore be at some distance from the lordship centre that they served. The parks functioned as deer farms, supplying venison for the lord’s table, with a variable amount of actual hunting. Parks could also include rabbit warrens and fishponds, also supplying food for the lord. Lodges within the parks supplied accommodation for a parker and/or a visiting lord. Some parks were in existence by 1086, but the majority appear to have been active in the period 1200-1400. Most were ‘disparked’ by the 16th Century and turned over to agriculture, but the legacy in the landscape can survive, in terms of names, field patterns and boundary features.

-

1.6. Former Marsh or Fenland

1.6. Former Marsh or FenlandAreas of inland marsh or fen that was enclosed before 1700. Enclosures frequently have curvilinear boundaries and drainage ditches, often reflecting pre-existing channels and streams.

-

1.7. Former Coastal Marsh

1.7. Former Coastal MarshAreas of coastal marsh that was enclosed before 1700. Enclosures frequently have curvilinear boundaries and drainage ditches, often reflecting pre-existing channels and creeks.

-

1.8. Planned Allotments

1.8. Planned AllotmentsAreas of fenland that were allotted to ‘adventurers’ (i.e. investors) in the 17th-century fen drainage enterprises. These are characterised by their straight-edged, geometric shapes associated with straight drains and roads. They may also have a farmstead set within a block of fields.

Type 2.0 18th Century and Later Enclosure

Advances in farming techniques, allied to significant social changes concerning the holding of land resulted in the ‘agricultural revolution’ of the 18th century. Prominent amongst the changes was the ending of the system of common-field farming whereby farmers cultivated separately-owned strips in large ‘open’ fields. Some common fields were enclosed by means of parliamentary acts, while others were enclosed by agreement. This type of ‘planned’ enclosure resulted in a landscape with regularly-shaped units with straight boundaries. Boundaries are usually composed of singlespecies hedges (usually hawthorn) or tree lines (e.g. the ‘pine lines’ of Breckland). Common fields were present in large parts of north-west Suffolk and, to a lesser extent, in the Stour Valley and the Sandlings, but were much less frequent in other parts of Suffolk, being absent in many parts of south Suffolk. Agricultural advancements in draining, fertilising and irrigation also resulted in the conversion of areas of common pasture, heath, fen and marsh to arable.

-

2.1. Former Common Arable or Heathland

2.1. Former Common Arable or HeathlandFields formed from land that was previously farmed as individually owned strips in large common or ‘open’ fields. Field shapes are frequently rectangular with straight boundaries, as a result of having been laid out to measured plans by surveyors. In the Breckland region of north-west Suffolk there temporary intakes from the heaths (called 'brecks'), which were cultivated for a short time and then abandoned to slowly recover their fertility. Similar temporary intakes occurred in the Sandlings of south-east Suffolk. As a result of this practice, the dividing line between heathland and common fields can be difficult to distinguish, hence the inclusion of heathland in the title of this sub-type.

-

2.2. Former Common Pasture, Built Margin

2.2. Former Common Pasture, Built MarginPastures of this type were usually called greens, but can also be termed tyes (in south Suffolk only) or commons. They are normally situated on poorly-drained clay plateaux and are medieval in origin. The greens were usually surrounded by substantial ditches, often water-filled and hedged on the outer margin, which frequently survive as substantial landscape features. Enclosure was often achieved though parliamentary acts and frequently involved the insertion of distinctive straight roads through the centres of the former greens. New straight boundaries were laid off at right-angles to these roads and many of the smaller land parcels were utilised as house plots. This leads to a distinctive landscape where the older houses are set back from the road on the old margin, reached by a series of individual driveways, and newer house flanking the inserted road. Deserted house sites, often showing now only as scatters of pottery, also occur on the margins.

-

2.3. Former Common Pasture, Open Margin

2.3. Former Common Pasture, Open MarginFields formed from the enclosure and sub-division of areas of common pasture that were not a focus for settlement and therefore, now and historically, had few or no houses on their margins. Common pastures of this type were frequently either heaths on impoverished dry sandy soils or wet riverine grasslands.

-

2.4. Former Post-medieval Deer Park

2.4. Former Post-medieval Deer ParkParkland designed to appear semi-natural with clumps of trees within extensive grassland and frequently fringed by belts of trees to give privacy and to exclude unwanted views. Usually designed as the setting for a great house and laid out to give vistas from that house. Lakes and decorative buildings or structures can form part of the layouts. Entrances are often guarded by lodges. Most examples are 18th or 19th century in date, though earlier examples do occur. Traces of earlier landscapes, like trees that were formerly part of field hedges sometimes can be detected.

-

2.5. Former Marsh or Fenland

2.5. Former Marsh or FenlandLand reclaimed, through drainage and embankment, from inland marsh or fen and converted into farmland, usually pasture, but also arable when conditions are suitable. The field pattern usually appears planned, with straight ditches or drains. The land may previously have been held in common and may have been subject to earlier reclamation attempts.

-

2.6. Former Coastal Marsh

2.6. Former Coastal MarshLand reclaimed, through drainage and embankment, from coastal marsh and converted into farmland, usually pasture, but also arable when conditions are suitable. The drainage pattern usually appears planned, with straight ditches or drains. Substantial sea banks normally protect the reclaimed land. Sluices and pumping mills frequently occur. The land may previously have been held in common and may have been subject to earlier reclamation attempts.

-

2.7. Woodland Clearance

2.7. Woodland ClearanceFields created as a result of woodland clearance. The former wood boundary often survives as a curving field boundary, but internal subdivisions usually have straight boundaries.

-

2.8. Former Warren

2.8. Former WarrenFormer rabbit warrens enclosed and converted into farmland. Warrens, often sited on heathland, are documented from the 12th century onwards, but few, if any, survived in active management beyond the early part of the 20th century. Warrens were frequently enclosed within earthen banks, which may survive as field boundaries. Disused warrener’s lodges may also occur

-

2.9. Former Heath

2.9. Former HeathThe enclosure and conversion to arable or pasture of land that was formerly of Sub-type 8.1 (Unimproved land – heath or rough pasture): Areas of natural or semi-natural vegetation (particularly grass and heather) on dry, acidic soils. Historically too dry and impoverished for arable cultivation, they were managed mainly as areas of sheep pasture (often called ‘sheep walks’). Some areas of heathland had experienced intermittent arable cultivation (termed ‘brecks’ in Breckland and sometimes as ‘ol(d)land’ elsewhere). Where there has been minimal cultivation there are often earthworks of archaeological interest, such as prehistoric burial mounds

-

2.10. none

-

2.11. Former Mere

2.11. Former MereFormer mere or natural lake that has been drained and converted into arable land. Parts of the former mere outline may survive in the land boundaries, but boundaries within the former mere will tend to take the form of straight drains

Type 3.0 Post-1950 Agricultural Landscape

Areas that have had their character altered as a result of agricultural changes in the post-war period. Historic field patterns have disappeared or been weakened through the removal and remodelling of hedges and other field boundaries. Other important changes are in land use, as in the conversion of meadows into arable land. Overall, these changes have produced 20th-century landscapes, but aspects of their previous character can be determined by reference to earlier mapping, such as the 1st edition Ordnance Survey (see maps provided) or tithe maps. The following subdivisions are based on their earlier character, some traces of which frequently remain.

-

3.1. Boundary Loss from Random Fields

3.1. Boundary Loss from Random Fields20th-century boundary loss from fields formerly of Sub-type 1.1 (random fields): Landscapes made up of fields that have an irregular pattern (i.e. without any dominant axis). Many were in existence by the medieval period, but could be earlier. Boundaries usually take the form of species-rich hedges (normally coppiced not laid) with associated ditches and banks. Areas with this field pattern are probably some of our earliest farming landscapes

-

3.2. Boundary Loss from Rectilinear Fields

3.2. Boundary Loss from Rectilinear Fields20th-century boundary loss from fields formerly of Sub-type 1.2 (Pre-18th-century enclosure – rectilinear fields): This is not a dominant type in Suffolk. Landscapes of this type are made up of fields that tend to be small and rectilinear in shape, forming patterns that resemble the brickwork in a wall. They tend to exist in isolated pockets within more extensive areas of other types of early enclosure, and probably indicate relatively late episodes of field creation or re-organisation, although still pre-18th century, within earlier surroundings.

-

3.3. Boundary Loss from Long Co-Saxial Fields

3.3. Boundary Loss from Long Co-Saxial Fields20th-century boundary loss from fields formerly of Sub-type 1.3 (Pre-18th-century enclosure – long co-axial fields): Landscapes made up of fields where a high proportion of the boundaries share a dominant axis. This takes the form of long, slightly sinuous lines that run roughly parallel to each other for considerable distances. These lines usually run at right angles to a significant watercourse. Co-axial systems are not all of the same date – some in valley-side positions may represent very early farming boundaries, but others on the clay plateaux are likely to be medieval in date (as in parts of the South Elmhams).

-

3.4. Boundary Loss from Irregular Co-Axial Fields

3.4. Boundary Loss from Irregular Co-Axial Fields20th-century boundary loss from fields formerly of Subtype 1.4 (Pre-18th-century enclosure – irregular co-axial fields): Landscapes where many of the boundaries share a common axis. They share many of the characteristics of long co-axial fields (sub-type 1.3) but lack their overall regularity and their boundaries are often only approximately parallel. The systems vary in size, merge in and out of one another, and generally fail to follow one particular aspect or angle. In some cases these systems represent the early, piecemeal, enclosure of common fields.

-

3.5. Boundary Loss from Post-1700 Fields

3.5. Boundary Loss from Post-1700 Fields20th-century boundary loss from fields that were enclosed after 1700. This sub-type includes both fields created through the enclosure of common fields and fields created through the enclosure of other types of land. Boundaries, where they survive, are usually straight and are composed of single-species hedges.

-

3.6. Woodland Clearance

3.6. Woodland ClearanceAgricultural land created through woodland clearance in the post-war period. The former wood boundary may survive as a curving field boundary, but internal subdivisions usually have straight boundaries.

-

3.7. Arable on Former Meadow

3.7. Arable on Former Meadow20th-century conversion to arable of land that was formerly of Sub-type 5.1 (Meadow or managed wetland – meadow): Seasonally wet grassland that is mown for hay and/or grazed by animals. Normally found alongside rivers and streams and characteristically takes the form of long and narrow land parcels that run parallel to the watercourses. Often hedged on the dry-land side, but with ditched internal sub-divisions that often have a drainage function

-

3.8. Arable on Former Heath

3.8. Arable on Former Heath20th-century conversion to arable of land that was formerly of Sub-type 8.1 (Unimproved land – heath or rough pasture): Areas of natural or semi-natural vegetation (particularly grass and heather) on dry, acidic soils. Historically too dry and impoverished for arable cultivation, they were managed mainly as areas of sheep pasture (often called ‘sheep walks’). Some areas of heathland had experienced intermittent arable cultivation (termed ‘brecks’ in Breckland and sometimes as ‘ol(d)land’ elsewhere). Where there has been minimal cultivation there are often earthworks of archaeological interest, such as prehistoric burial mounds.

-

3.9. Boundary Loss, Enclosed Medieval Deer Park

3.9. Boundary Loss, Enclosed Medieval Deer Park20th-century boundary loss from an area of land that was formerly of Sub-type 1.5 (Pre-18th-century enclosure – former medieval deer park): Deer parks were important symbols of lordship in the medieval period and normally consisted of areas of woodland, wood pasture and open grassland (launds), bounded by banks and ditches with hedging and/or wooden fences to form a ‘park pale’. Park pales frequently have curved outlines as this was the most economic way of enclosing large areas. Deer parks were frequently situated on upland clay areas unsuited to agriculture and can therefore be at some distance from the lordship centre that they served. The parks functioned as deer farms, supplying venison for the lord’s table, with a variable amount of actual hunting. Parks could also include rabbit warrens and fishponds, also supplying food for the lord. Lodges within the parks supplied accommodation for a parker and/or a visiting lord. Some parks were in existence by 1086, but the majority appear to have been active in the period 1200-1400. Most were ‘disparked’ by the 16th Century and turned over to agriculture, but the legacy in the landscape can survive, in terms of names, field patterns and boundary features

Type 4.0 Common Pasture

Areas of pasture that were/are grazed communally. The number and types of animals that were allowed on the pastures was regulated by the manorial courts and the common-right holders. These common rights can be termed gates, goings, shares or stints. Other common rights can include rights to take fuel (often gorse or ‘furze’) and clay, sand or other ‘stone’.

-

4.1. Built Margin

4.1. Built MarginCommon pastures on the claylands were usually enclosed by a substantial ditch, often water-filled, and can be hedged on the outer margin. Their shapes can be very varied, but they frequently have funnel-shaped extensions where roads enter them, presumably to help with the herding of animals. Usually called greens, they can also be termed tyes (in south Suffolk only) or commons. Small greens are often triangular and arranged around the junction of three roads. Large greens (over 20ha) are a particular feature of the clay plateaux of north Suffolk. Farmsteads and cottages fringe the margins of the greens and these usually have or had common rights attached to them. Deserted house sites, often showing now only as scatters of pottery, also occur on the margins. Windmills frequently occur within or on the margin of greens. Greens seem to have been established from the 12th century onwards and usually occur on poorly-drained clay plateaux.

-

4.2. Open Margin

4.2. Open MarginAreas of common pasture that were not a focus for settlement, and therefore, now and historically, had few or no houses on their margins. Common pastures of this type are frequently either heaths on impoverished sandy soils or wet riverine grasslands. There is therefore an overlap with types 5 (meadow or managed wetland) and 8 (unimproved land).

Type 5.0 Meadow or Managed Wetland

Wet grassland or land with other non-woody wetland vegetation that is enclosed and managed.

-

5.1. Meadow

5.1. MeadowSeasonally wet grassland that is mown for hay and/or grazed by animals. Normally found alongside rivers and streams and characteristically takes the form of long and narrow land parcels that run parallel to the watercourses. Often hedged on the dry-land side, but with ditched internal sub-divisions that often have a drainage function.

-

5.2. Meadow with Modern Boundary Loss

5.2. Meadow with Modern Boundary LossBoundary loss from seasonally wet grassland that is mown for hay and/or grazed by animals. Meadows are normally found alongside rivers and streams and characteristically take the form of long and narrow land parcels that run parallel to the watercourses. The lost boundaries can be either the hedges on the dry-land side or the ditched internal sub-divisions that often had a drainage function.

-

5.3. Managed Wetland

5.3. Managed WetlandWetland with a non-woody vegetation that is enclosed and managed. This sub-type includes grazed marshland and managed reed beds.

-

5.4. Former Mere

5.4. Former MereFormer mere or natural lake that has been drained and converted into pasture or other form of managed wetland. Parts of the former mere outline may survive in the land boundaries, but boundaries within the former mere will tend to take the form of straight drains.

Type 6.0 Horticulture

Includes orchards, nursaries, allotments, market gardens and plotlands.

-

6.1. Orchard

6.1. OrchardLand planted with fruit trees, often arranged in straight rows.

-

6.2. Nurseries with Glass Houses

6.2. Nurseries with Glass HousesLand used for commercial plant growing, involving the use of glass-houses.

-

6.3. Allotments

6.3. AllotmentsAn area divided into small plots which are annually leased by individuals to grow flowers and vegetables. 19th-century and later in date.

-

6.4. Market Gardens

6.4. Market GardensLand used for the commercial growing of vegetables in small-scale operations.

-

6.5. Plotlands

6.5. PlotlandsSmall plots of agricultural land sold to people, mainly from the poorer districts of London, in the first half of the 20th century and used as smallholdings and/or homesteads that were often small bungalows or shacks, often without services and served by poorly-maintained roads. The practice was ended by the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act. Particularly to be found in Essex (Basildon, Jaywick Sands etc). Included are the lands of the Newbourne Land Settlement Scheme for unemployed miners in Suffolk (1935-?82).

Type 7.0 Woodland

Woodland has been part of the Suffolk landscape since prehistoric times. In the historical period, woodland was a fundamental rural resource, providing wood for fuel and and timber for construction purposes, as well as a place for hunting, rough pasture and swine forage.

-

7.1. Ancient Woodland

7.1. Ancient WoodlandAreas of deciduous woodland of ‘ancient’ character. This includes all the woodland defined as ‘ancient’ in the Nature Conservation Council survey of 1992. In their view, ancient woodland sites are those which have had a continuous woodland cover since at least 1600 to the present day and to have only been cleared for ‘underwood’ (coppice poles and/or firewood) and/or timber production. A wood present in 1600 was likely to have been in existence for centuries. This date was adopted as a threshold for two important reasons: firstly, it roughly marked the time when plantation forestry was widely adopted and, secondly, the period when detailed maps first start to appear. Ancient woods were frequently enclosed within wood banks and may contain internal sub-divisions

-

7.2. Former Medieval Deer Park

7.2. Former Medieval Deer ParkDeer parks were important symbols of lordship in the medieval period and normally consisted of areas of woodland, interspersed with more open areas of wood pasture and grassland glades (launds), bounded by banks and ditches with hedging and/or wooden fences to form a ‘park pale’. Park pales frequently have curved outlines as this was the most economic way of enclosing large areas. Deer parks were frequently situated on upland clay areas unsuited to agriculture and can therefore be at some distance from the lordship centre that they served. The parks functioned as deer farms, supplying venison for the lord’s table, with a variable amount of actual hunting. Parks could also include rabbit warrens and fishponds, also supplying food for the lord. Lodges within the parks supplied accommodation for a parker and/or a visiting lord. Some parks were in existence by 1086, but the majority appear to have been active in the period 1200-1400. Many had fallen into disuse by the 16th century, but some continued in existence as woodland.

-

7.3. Modern Plantation on Former Arable

7.3. Modern Plantation on Former ArablePlantations, often coniferous, on land that can be shown, on map evidence, to have been farmland in the 19th or 20th century. The plantations usually form rectangular blocks or other regular linear or geometric shapes.

-

7.4. Modern Plantation on Former Common Arable or Heath

7.4. Modern Plantation on Former Common Arable or HeathPlantations, often coniferous, on land that was formerly common arable land or intermittently cultivated heathland. The plantations were often introduced when the land was enclosed in the 18th and 19th centuries and usually take the form of rectangular blocks or other regular linear or geometric shapes. This subtype also includes much of the substantial coniferous forests that were planted by the Forestry Commission from the 1920s onwards in Breckland (Thetford Forest) and the Sandlings (Rendlesham and Dunwich Forests).

-

7.5. Modern Plantation on Former Common Pasture

7.5. Modern Plantation on Former Common PasturePlantations established on former commons or greens after their enclosure, usually in the 18th or 19th centuries. The plantations usually form rectangular blocks or other regular linear or geometric shapes. Woodland – modern plantation on former informal park (Sub-type 7.6). Plantations established on former informal parkland after its conversion to farmland, usually in the 20th century. The plantations are usually rectangular in plan

-

7.6. Modern Plantation on Former Informal Park

7.6. Modern Plantation on Former Informal ParkPlantations established on former areas of informal parkland after the park was converted to other uses. Frequently these plantations are of mid-20th century date, coniferous, and form rectangular blocks or other regular linear or geometric shapes.

-

7.7. Modern Plantation on Former Warren

7.7. Modern Plantation on Former WarrenPlantations established on former rabbit warrens after their enclosure, often in 20th century. The plantations usually form rectangular blocks or other regular linear or geometric shapes. This sub-type includes substantial areas of the coniferous forest that was planted by the Forestry Commission from the 1920s onwards in Breckland (Thetford Forest). Warrens are documented from the 12th century onwards, but few, if any, survived in active management beyond the early part of the 20th century. Warrens were frequently enclosed within earthen banks, which often survive within, or surround the plantations. Disused warreners’ lodges can also occur (as at Mildenhall).

-

7.8. Wet Woodland or Alder Carr

7.8. Wet Woodland or Alder CarrThis sub-type includes both ancient wet woodland characterised by a predominance of alder (and sometimes specifically named as ‘alder carr’) and more recent natural regeneration in poorly maintained or grazed meadows

-

7.9. Modern Plantation on Former Meadow

7.9. Modern Plantation on Former Meadow20th century plantations on former meadows.

-

7.10. none

-

7.11. Modern Plantation on Former Heath

7.11. Modern Plantation on Former HeathPlantations on former heathland. The plantations usually form rectangular blocks or other regular linear or geometric shapes.. This sub-type includes areas of coniferous forest that was planted by the Forestry Commission from the 1920s onwards in Breckland (Thetford Forest) and the Sandlings (Rendlesham and Dunwich Forests).

-

7.12. Wooded Common

7.12. Wooded CommonAreas of common land that have traditionally been managed as woodland, or natural regeneration on insufficiently grazed common pastures.

-

7.13. Park Wood

7.13. Park WoodAreas of woodland planted as part of post-medieval landscape parks. Includes both internal groves and tree belts that act as the park boundaries.

-

7.14. Modern Plantation on Former Fenland

7.14. Modern Plantation on Former FenlandLargely 20th-century plantations on drained former fenland.

Type 8.0 Unimproved Land

Areas of natural or semi-natural vegetation that have not undergone agricultural improvement. These are frequently areas of great significance for wildlife and may be designated as nature reserves.

-

8.1. Heath or Rough Pasture

8.1. Heath or Rough PastureAreas of natural or semi-natural vegetation (particularly grass and heather) on dry, acidic soils. Historically too dry and impoverished for arable cultivation, they were managed mainly as areas of sheep pasture (often called ‘sheep walks’). Under the foldcourse system, sheep were put to graze on the heaths during the day and folded (enclosed within temporary hurdle fences) overnight on the arable land to enrich it with their dung. Some areas of heathland have experienced intermittent arable cultivation (termed ‘brecks’ in Breckland and sometimes as ‘ol(d)land’ elsewhere). Where there has been minimal cultivation there are often earthworks of archaeological interest, such as prehistoric burial mounds. Lack of grazing in the 20th century has resulted in the growth of scrub and bracken on many heaths.

-

8.2. Heath, Former Warren

8.2. Heath, Former WarrenAreas of natural or semi-natural vegetation (particularly grass and heather) on dry, acidic soils that were used as rabbit warrens. Warrens are documented from the 12th century onwards, but few, if any, survived in active management beyond the early part of the 20th century. Warrens were frequently enclosed within earthen banks and may contain mounds for the rabbits to burrow into. Internal lodges for the warreners also occur. Some of the largest warrens occurred in Breckland (e.g. Lakenheath Warren was 2300 acres (931 ha).

-

8.3. Freshwater Fen or Marsh

8.3. Freshwater Fen or MarshAn inland marsh occupying low-lying poorly-drained wet land. Fens were formerly a particular feature of the extreme north-west of the county where they covered many thousand acres, forming the south-eastern edge of the extensive fenland basin that stretched westward into Cambridgeshire and northwards into Norfolk. Major drainage and reclamation works started in the 17th century and little undrained land remained by the mid 19th century. Fens or marshes also occur in river valleys. Historically, the seasonally drier areas were managed for summer grazing and the wetter areas were cropped for reeds and used for wildfowling, eel fisheries and peat digging. Surviving fens/marshes are now frequently nature reserves and are only cropped to preserve their ecological integrity.

-

8.4. Coastal Marsh

8.4. Coastal MarshLow-lying areas adjacent to the sea or estuarine inlets, subject to regular or occasional salt-water inundations. Coastal marshes were historically an important part of coastal economies, providing reeds, eels and seasonal rough pasture. Many have been drained and enclosed during the last three hundred years. Those that remain are frequently nature reserves now.

-

8.5. Intertidal Land

8.5. Intertidal LandLow lying coastal areas subject to regular tidal inundations. Economically this landscape type has been utilised as a base for fish traps which capitalise on the tidal flow, a process which is likely to have been occurring since at least the Anglo-Saxon period, and possibly much earlier. This landscape type is physically unstable, and usually too costly and impractical to reclaim for agriculture. Reclamation for high capital industrial projects, such as quayside development around Felixstowe, can sometimes occur.

-

8.6. Shingle Spit

8.6. Shingle SpitLinear accumulations of shingle on the coast, as at Orford Ness where there is an eleven-mile long spit, the largest formation of its kind on the east coast.

-

8.7. Mere

8.7. MereA natural lake, often resulting from depressions in the post-glacial landscape. Meres are likely to contain sediments with a high palaeo-enviromental value.

-

8.8 Broad

8.8 BroadA large body of water resulting from the flooding of extensive medieval peat diggings or turbaries. The peat or ‘turf’ was extracted and dried for fuel. Broads are best-known from those in Norfolk (giving rise to the area name of ‘Broadland’ or ‘The Broads’) but also extend along the Waveney and its tributaries into Suffolk. They have been classified as ‘by-passed broads’ where they are on the sides of major river valleys (eg. Barnby Broad in the Waveney valley) and ‘side-valley broads’ where they occupy tributary valleys (eg. Outon Broad). Some were later used for other purposes, eg. as duck decoys, as at Fritton Decoy

Type 9.0 Post-medieval Park and Leisure

Open areas, frequently grassed, and sometimes with terrain landscaping. Where trees, patches of woodland, water features or built structures occur they frequently have designed positions or shapes that are intended to contribute to the aesthetic character of the landscape.

-

9.1. Formal Park or Garden

9.1. Formal Park or GardenA park or garden with a formal or geometric arrangement. These are usually late-17th- or early 18th-century in date and normally associated with a great house and having an axial relationship to it.

-

9.2. Informal Park

9.2. Informal ParkParkland designed to appear semi-natural with clumps of trees within extensive grassland and frequently fringed by belts of trees to give privacy and to exclude unwanted views. Usually designed as the setting for a great house and laid out to give vistas from that house. Lakes and decorative buildings or structures can form part of the layouts. Entrances are often guarded by lodges. Most examples are 18th or 19th century in date, though earlier examples do occur. Traces of earlier landscapes, like trees that were formerly part of hedge lines can sometimes be detected.

-

9.3. Modern Leisure

9.3. Modern LeisureThe growth of leisure as an ‘industry’ during the 20th century has led to the creation of many ‘leisure landscapes’ within previously rural or marginal areas. This sub-type includes extensive modern landscape features such as golf courses, playing fields and camp/caravan sites.

Type 10.0 Built Up Area

Includes towns, villages, hamlets, green edge or infill, house or farmstead, isolated churches.

-

10.1. Unspecified

10.1. UnspecifiedA built up area of unspecified type or size. [This type is also being used temporarily for all the former undifferentiated 10.0 land types].

-

10.2. Town

10.2. TownLarge settlement with urban functions. Historically, this sub-type includes the places that had functioning markets.

-

10.3. Village

10.3. VillageSubstantial groups of houses associated with a parish church.

-

10.4. Hamlet

10.4. HamletSmall groups of houses.

-

10.5. Green Edge or Infill

10.5. Green Edge or InfillHouses on the edge of greens or inserted into former greens after their enclosure. Greens seem to have been established from the 12th century onwards and usually occur on poorlydrained clay plateaux.

-

10.6. House or Farmstead

10.6. House or FarmsteadAn individual house or a farmstead with its associated agricultural buildings.

-

10.7. Isolated Church

10.7. Isolated ChurchMedieval churches which stand by themselves.

Type 11.0 Industrial

Land used for industrial purpose.

-

11.1. Current Industrial Landscape

11.1. Current Industrial LandscapeAreas in active use for an industrial purpose.

-

11.2. Disused Industrial Landscape

11.2. Disused Industrial LandscapeAreas in former use for an industrial purpose.

-

11.3. Current Mineral Extraction

11.3. Current Mineral ExtractionAreas in active use for mineral extraction. Minerals extracted are, in this region, usually, sand, gravel, clay and chalk.

-

11.4. Disused Mineral Extraction

11.4. Disused Mineral ExtractionAreas in former use for mineral extraction. Minerals extracted were, in this region, usually, sand, gravel, clay and chalk.

-

11.5. Water Reservoir

11.5. Water ReservoirArea used for the storage of water, either for human use or for farmland irrigation.

Type 12.0 Post-medieval Military

Land used for substantial military establishments.

-

12.1. Current Military

12.1. Current MilitaryLand used for military establishments. Particularly prominent in this region are the large 20th century air bases, as at Lakenheath and Mildenhall.

-

12.2. Disused Military

12.2. Disused MilitaryLand formerly used for military establishments.

Type 13.0 Ancient Monument

Land managed as an ancient monument

-

13.1. Ancient Monument

13.1. Ancient MonumentLand managed as an ancient monument, eg. Framlingham Castle

Type 14.0 Communications

Land used for major communication routes.

-

14.1. Major Roads

14.1. Major RoadsSubstantial trunk roads that are major landscape features.

-

14.2. Railway

14.2. RailwayRailway lines in current use.