Introduction

After the withdrawal of the Romans, there was little evidence of any continuous Saxon settlement in Ipswich. It wasn't until the 7th century that Saxon occupation developed on the site of the present town. Around 720 AD the town expanded, covering a 50ha area, with a newly laid street pattern, significant waterfront activity, craft production and international trade. Ipswich became one of the most important Anglo-Saxon towns in England. The 9th century brought a period of great cultural change after Scandinavian invasion in 865 AD; Ipswich remained under Scandinavian rule and settlement until the West Saxon conquest in 920.

Click on the headings below to find out more about Ipswich in the Saxon period.

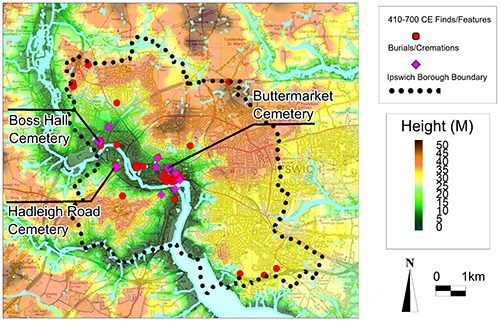

Immediately following the collapse of Roman rule in Western Europe, evidence for activity in Ipswich is sparse. Two brooches of early 5th-century date, found during excavations at School Street in 1983-5, probably represent items scavenged from a site of this date yet to be found in the Borough. There is some indication of activity around this time in the ruins of the Castle Hill Roman villa but nothing as yet to indicate permanent occupation.

A large cemetery of late 5th to early 7th century date, consisting of 159 inhumation graves and 13 cremations, was discovered in 1906 during ground levelling work at Hadleigh Road, 300m west of the River Gipping at Handford Bridge. A closely associated settlement was partially excavated in 2003, uncovering ten buildings including both halls and sunken-featured buildings (SFBs).

A second cemetery of 5th to early 7th century date was partially excavated on the Boss Hall Industrial estate in 1990 and 2014. Over 20 inhumation burials and 5 cremations have been found with further burials likely to be uncovered on adjacent land in future. Traces of contemporary occupation on the nearby Tannery site on Bramford Road probably indicate the associated settlement. Another possible settlement of this date is suggested by a brooch and pottery found at Waller’s Grove on the Chantry Estate in 1950.

All known Saxon (410-700) sites in the borough of Ipswich;

During the 7th century, the focus of activity moved to the site of the present town. This comprises a settlement, north of the river crossing at Stoke Bridge, and associated cemeteries on the higher ground to the north and south of the river in Stoke.

The best evidence of the settlement came from the Greyfriars Road (Novotel) site where two SFBs and many rubbish pits were associated with handmade pottery and imported Frankish wares. The distribution of handmade pottery suggests that occupation covered some 15hectares, north of the river, up to the line of Silent Street, Tacket Street and Lower Orwell Street.

North of this occupation, contemporary inhumation burials have been excavated at a number of sites: Foundation Street (2 graves), Bond Street (3 graves) and south of the Buttermarket (71 graves). An extensive radiocarbon dating programme carried out on the Buttermarket graves provided a date range of c.610/635 to c.680/690 AD. The graves were unusual compared with other contemporary cemeteries in England. Men, women and children commonly laid in coffins or containers and many of the graves were lined with wooden structures or linings. In two cases, the containers appeared to be small boats. Some of the burials were surrounded by penannular ditches, probably indicating that they were covered by mounds or small barrows and at least six individuals were buried with weapons or with jewellery and girdle assemblages. Three of the male burials had belt suites most closely paralleled in burials in northern France and Belgium.

The cemetery in Stoke, found on the Stoke Quay site, comprised 20 inhumation burials, including seven under barrows, dating from the late 6th to early eighth century.

Around 720 AD, the town expanded to cover about 50 hectares. This involved an extension over the heathland burial ground to the north, along a newly laid-out grid-iron pattern of streets, and south of the river into Stoke. Extensive excavation has shown that the economy was based on craft production and international trade.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire in Western Europe in the early 5th century, town life in England largely disappeared. It was not until the early 7th century that it reappeared in the form of a series of emporia established around the North Sea coast. Hamwic (Southampton) served Wessex, Lundenwic (London) served various kingdoms before becoming the national capital, Eoforwic (York) served Northumbria and Gipeswic (Ipswich) served East Anglia (and Mercia during the time of Mercian supremacy). Excavations in the emporia of both Hamwic and Lundenwic have shown almost identical settlements to that at Gipeswic. These are England’s earliest towns, with unbroken occupation up to the present day. Only Ipswich remains on exactly the same site as its Middle Saxon predecessor.

These towns forged connections across the North Sea. Ipswich was trading mainly with Dorestad, on the river Rhine, Hamwic was trading mainly with Quentovic, in the Pas de Calais, and York mainly with the Scandinavian emporia at Hedeby (now in Denmark) and Birka, in Sweden. Each a centre of commerce and cultural exchange, these places were pivotal in the development of nations and international relationships.

Craft Production and International Trade

Image: Excavated Ipswich ware pottery kiln at Stoke Quay

Craft production was dominated by the Ipswich Ware pottery industry. It was a large-scale enterprise, concentrated in the north-east corner of the town along Carr Street, but outlying kilns have also been excavated at the Buttermarket and south of the river in Stoke. The importance of the Ipswich ware industry is demonstrated by its presence in the archaeology, not only of the entire kingdom of East Anglia but as far as the West Country, Yorkshire, London and Kent. Most sites across the town also have evidence of bone and antler working, spinning and weaving, and metalworking. Evidence for leatherworking only survives in the waterlogged deposits of the waterfront but it must have common in the rest of the town.

Craft production was dominated by the Ipswich Ware pottery industry. It was a large-scale enterprise, concentrated in the north-east corner of the town along Carr Street, but outlying kilns have also been excavated at the Buttermarket and south of the river in Stoke. The importance of the Ipswich ware industry is demonstrated by its presence in the archaeology, not only of the entire kingdom of East Anglia but as far as the West Country, Yorkshire, London and Kent. Most sites across the town also have evidence of bone and antler working, spinning and weaving, and metalworking. Evidence for leatherworking only survives in the waterlogged deposits of the waterfront but it must have common in the rest of the town.

Ipswich was a main port for international trade. Imported goods include hone stones from Norway, lava querns from the Rhineland and pottery from Belgium and Northern France. Over 6000 sherds representing over 900 vessels have been found to date, a much larger quantity than is found in contemporary sites further inland. Most of this pottery probably represents foreign traders in residence, but the fancier vessels were most likely in transit to the tables of the East Anglian aristocracy. Wool and textiles were exported, while wine was imported in wooden barrels, some of which have been found preserved as the linings of shallow wells across the town. An example from Lower Brook Street matched the tree ring pattern of the Mainz area of Germany.

Excavations at Buttermarket and Foundation Street

Evidence for the townscape of the Middle Saxon town comes from two areas of large scale excavation south of the Buttermarket(St Stephen’s Lane) and either side of Foundation Street.

At the Buttermarket, in the centre of the town, a continuous row of rectangular, surface-laid timber buildings was found hard up against the street edge. In their backyards, various crafts were in evidence including weaving, bone and antler working, metalworking (silver, copper alloy, iron) and potting in the form of a single Ipswich ware kiln.

A different picture emerged either side of Foundation Street, on the eastern edge of the Middle Saxon town. Here, there were fewer buildings, set back from the street and within fenced enclosures. Environmental evidence indicates more emphasis on agricultural activities here including livestock and cereal cleaning. This implies that the concept of a town centre, with more commercial activity, and a periphery with a more agricultural function, may have existed from the start of urban life in England but this needs testing by further excavation.

Image: Aerial view of excavations at the Butter Market, Ipswich

Burial Grounds

Christian burial grounds were also established in this period. Two are known to date: on the western margin of occupation in the Elm Street area, and south of the river at Philip Road. Human remains from both sites have been radiocarbon-dated to this period. So far there has been no archaeological evidence for the foundation of churches in Ipswich in this period. St Peter’s has been suggested as the Minster church and St Mildred’s, on the Corn Hill, may have been a royal chapel (removed for the construction of the Town Hall in the 19th century).

Image: Reconstruction of Middle Saxon Enclosure at Whitehouse Road.

On the Waterfront

During this period, there was significant activity along the north bank of the river Orwell. Excavations at Bridge street in 1981 revealed a sequence of timber waterfront revetments dating from the seventh century onwards. The Middle Saxon waterfronts consisting of simple post and wattle hurdle construction, were little more than a bank protection to provide dry land on which to embark from the shallow draft boats of the period. More complex timber structures were found more recently during excavations at the Cranfields Mill site, south of Key Street.

The Wider Borough

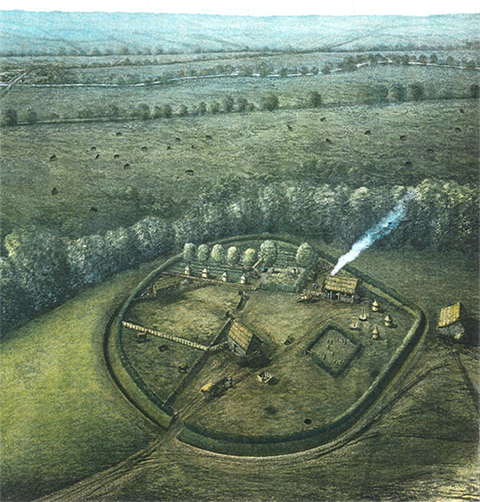

In the wider Borough, evidence of Middle Saxon activity has been found at a number of locations. A small settlement was excavated on the Whitehouse Industrial Estate in 1995. It lay within a ditched, roughly circular enclosure 90m in diameter, containing two large buildings and a small cemetery.

Other Middle Saxon settlements may be indicated by Ipswich ware pottery finds across the Borough but none of the sites have been investigated and they may have resulted from the manuring of arable fields with rubbish from the town.

The Scandinavian invasion of England in 865 AD culminated in permanent settlement in Eastern England. Guthrum, one of the principal Scandinavian leaders, settled East Anglia from 879-880 AD and Scandinavian rule lasted until 920 AD when the West Saxons regained the area.

This period (880-920 AD) is one of great cultural change in Ipswich, reflecting Scandinavian rule and settlement. The town was surrounded with defences for the first time, which involved the closure and diversion of some streets and restricted access to three gates on the west north and east sides of the town. The sunken-featured building was re-introduced and craft activity increased markedly. Metalworking included both iron smelting, smithing and copper-alloy working. Moulds indicate brooch manufacture. It was also during this period that the Thetford ware pottery industry replaced Ipswich ware, though the industry remained mainly in the north-east area of the town, and kilns have been found along the south side of Carr Street, as well as single kilns at the west end of St Helen’s street and in Turret Lane, south of the Buttermarket. Thetford ware industries were also established in the new Anglo-Scandinavian towns of Thetford and Norwich.

From the West Saxon conquest in 920 AD to the Norman Conquest in 1066 AD, the town grew very little but remained one of the ten most important Anglo-Saxon towns. The street pattern was inherited from its Middle Saxon predecessor, modified only by the construction of the town defences. The townscape during this period became more uniform, with buildings set back normally 10-15 metres from the street front. The buildings continue to be sunken-featured but they increase in size and become two-storied with the sunken feature acting a cellar or half cellar.

The economy continued to be based on craft activity and international trade and Ipswich acquired a mint by the reign of Edgar (959-975 AD). Local and regional trade, westward to the east Midlands dominated the 10th century but international trade picked up again in the eleventh century.